ATTRACTING ATTENTION WITH RIDDLES

Are riddle advertisements a solution for the advertising overload?

Consumer's involvement with advertisements decreases because of the enormous information-overload. Advertisers are, therefore, challenged to devise new strategies to reach consumers. Consequently, more open ads appear in magazines. Open ads lack clear cut messages and because of that seem prone to multiple interpretations. However, it is unclear if openness in ads leads to higher advertising effectiveness. Paul Ketelaar, Marnix van Gisbergen and Ilse Vogelzang, researchers at the University of Nijmegen (department of Communication) and the media-selection agency 'The Media Edge' worked together to examine the effects of openness in advertisements.

Heightened media pressure

In magazine advertisements it is customary to use eye-catching headlines and a visible product to engage consumers and persuade them into buying the advertised brand. These advertisements frequently communicate with informational and obvious messages. Due to the heightened media pressure and media expenditure in our society, such a single advertising message might be buried into the enormous quantity of corresponding messages. Because of this, there is even a chance advertising will not reach consumers at all. To prevent this from happening a new development occurs, which is called 'open advertising'. However, if open ads result in higher advertising effectiveness is unclear. In which type of magazines these advertisements fit best, is also indistinct. In this research we examined the effects of open and closed ads, in different magazines, on involvement, recall and evaluation.

Advertising openness as a new strategy

Open ads lack clear cut messages and seem, therefore, prone to multiple different interpretations. However, no ad is entirely open or closed. There is a continuum in openness, so to speak. An open advertisement often consists out of a brand combined with an image. Although a headline is sometimes used, open ads usually do not rely on verbal explanation. While traditional ways of advertising often explicitly lead the consumer to a specific meaning, open ads do not. Instead the consumer has the liberty (intentionally or not) to extract multiple meanings from open ads, using their own personal frame of reference. This seems to be in conflict with the objectives of commercial communication; to persuade consumers as soon as possible. However, because open ads invite consumers to search for meaning and subsequently construct meaning, they might lead to feelings of power and joy. Moreover, information that needs some cognitive effort is retained from memory faster and better than information which is less actively processed. Consequently, openness in advertisements could increase involvement, evaluation and recall of advertisements. Open ads lack clear cut messages and seem, therefore, prone to multiple different interpretations. However, no ad is entirely open or closed. There is a continuum in openness, so to speak. An open advertisement often consists out of a brand combined with an image. Although a headline is sometimes used, open ads usually do not rely on verbal explanation. While traditional ways of advertising often explicitly lead the consumer to a specific meaning, open ads do not. Instead the consumer has the liberty (intentionally or not) to extract multiple meanings from open ads, using their own personal frame of reference. This seems to be in conflict with the objectives of commercial communication; to persuade consumers as soon as possible. However, because open ads invite consumers to search for meaning and subsequently construct meaning, they might lead to feelings of power and joy. Moreover, information that needs some cognitive effort is retained from memory faster and better than information which is less actively processed. Consequently, openness in advertisements could increase involvement, evaluation and recall of advertisements.

Trendy or mainstream magazine?

The increasing advertising overload in the media has led to an increase in different magazines. Media research is mainly focused at quantitative data like Gross Rating Points (GRP) and the reach of media. Less attention is paid to qualitative variables such as the characteristics of the content of the magazine in which an ad is inserted ('magazine context'). Media planners do not always get to see the advertisement in advance and, therefore, can not always take ad/context similarity into account. When media planners can take this factor into account, they often can not base their choices on qualitative research. Instead, they must rely on intuition. This study examines whether open ads are more appropriate for trendy magazines (with an open context) than mainstream (with a closed context) magazines.

Method

Two qualitative studies have been done. During the first study 56 female students had to write down all their thoughts, ideas and feelings concerning 3 open and 3 closed ads. They also had to indicate what they thought the ads were trying to communicate. The interpretations that derived from this study were used in the second study. In the second study the same six test ads were inserted in a trendy magazine (Strictly) and mainstream magazine (Viva), whereupon 18 female readers were asked to read through one of the magazines at their own pace. The categorization into trendy- and mainstream magazines was based on interviews with media planners

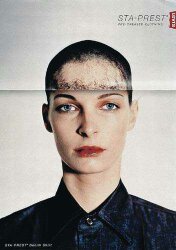

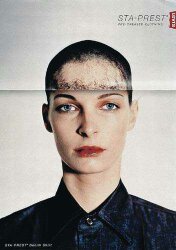

Results: small difference in recall

The open ads elicited more and more different interpretations than the closed ads (an average of twice as much). Furthermore, it was striking that many individual meanings were extracted from the ads. Just one open and one closed ad elicited the same interpretation for more than half of the women. Both the open and the closed ads elicited different interpretations which were all positive towards the brand. Remarkably, the second study showed that respondents were able to describe only two of the approximate 23 ads that appeared in the 'dummy' magazines. Recall of brands was even worse: the average number of brands recalled was one per person. Therefore, differences in recall between open ads and closed ads haven't been found. However, the open Levi's ad (see example) was mentioned considerable more often than the remaining ads. No notable differences were found between open and closed ads when measuring recognition. The Levi's ad was again a striking exception. Recognition of this particular ad was remarkably high because of the distinctive and dirty head that raised many questions.

More meanings

In comparison with the closed ads, the open ads induced more cognitive effort from the respondents. The open ads raised questions and with that a search for answers. The search for meaning was mainly caused by visual elements in the ads, like a bottle of perfume in a telephone ad or the bunch of keys in the lotion ad. While open and closed ads elicited literal descriptions, most respondents gave literal responses to closed ads. The average number of meanings extracted from the closed ads was about three, while the average number of extracted meanings from the open ads was about eight. Most of the interpretations extracted from the open ads referred to positive features of the product; interpretations of the closed ads referred to the intention to sell the product. Respondents ended their search for (other) meanings when they were convinced that they found the intended interpretation.

Increase in involvement

It appears that open ads increase involvement. High involvement seems to be a result of the mysteriousness of primarily the images in open ads. Because of the puzzling character of these images, open ads do not meet recipients' expectations. Other variables which appeared to influence involvement were: the product (“I'm not interested because I already purchased a cell phone”), the brand, Style Of Processing (“Considerable amount of text. I'm getting tired just by looking at it”) and Need For Cognition (“I enjoy trying to extract as many meanings as possible”). A striking result was that open ads did not fit the recipient's preconception of what those ads should look like for similar product categories. The closed ads did meet recipients' expectations. Expectations were based on the product category (“I expect to see phones or people talking on the phone when confronted with a phone ad”) and the brand being advertised (“Levi's always has those distinctive commercials”). Expectations were mainly based on respondents' prior experience with ads for certain products (“Ass and jeans are indissolubly linked”).

Increase in ad liking

The schema-inconsistency of open ads led to increased ad liking. Open ads were evaluated more positively than closed ads, although open ads also caused irritation in case of incomprehension. However, irritation was higher when caused by repeated exposure to the same “standard” (closed) ads for certain products. Openness in ads seems to be an important factor in evaluation, even more important than product or brand involvement. Open ads were liked more when embedded in a magazine with a congruent context, in this case a trendy magazine. Respondents perceived open ads in mainstream magazines as more outstanding, because of the contrasting magazine context. The former didn't apply to closed ads; these ads did not appear to be more notable in a trendy magazine.

In conclusion: trying to find the right balance

Is it valid to conclude that advertisers should communicate with open ads in magazines with a similar context? The answer is no, not yet; quantitative research is necessary to generalize these findings. Besides, the ad's complexity appears to be important. Respondents are willing to think about open ads, but not for too long. The idea is to find the right balance; providing sufficient “riddle” to ensure consumers are triggered to think about the ad and extract their own meaning. The tendency seems to be clear: open ads are evaluated more positively than closed ads. Consumers construct their own meaning(s) out of open ads, which are mostly positive for the brand.

|

Open ads lack clear cut messages and seem, therefore, prone to multiple different interpretations. However, no ad is entirely open or closed. There is a continuum in openness, so to speak. An open advertisement often consists out of a brand combined with an image. Although a headline is sometimes used, open ads usually do not rely on verbal explanation. While traditional ways of advertising often explicitly lead the consumer to a specific meaning, open ads do not. Instead the consumer has the liberty (intentionally or not) to extract multiple meanings from open ads, using their own personal frame of reference. This seems to be in conflict with the objectives of commercial communication; to persuade consumers as soon as possible. However, because open ads invite consumers to search for meaning and subsequently construct meaning, they might lead to feelings of power and joy. Moreover, information that needs some cognitive effort is retained from memory faster and better than information which is less actively processed. Consequently, openness in advertisements could increase involvement, evaluation and recall of advertisements.

Open ads lack clear cut messages and seem, therefore, prone to multiple different interpretations. However, no ad is entirely open or closed. There is a continuum in openness, so to speak. An open advertisement often consists out of a brand combined with an image. Although a headline is sometimes used, open ads usually do not rely on verbal explanation. While traditional ways of advertising often explicitly lead the consumer to a specific meaning, open ads do not. Instead the consumer has the liberty (intentionally or not) to extract multiple meanings from open ads, using their own personal frame of reference. This seems to be in conflict with the objectives of commercial communication; to persuade consumers as soon as possible. However, because open ads invite consumers to search for meaning and subsequently construct meaning, they might lead to feelings of power and joy. Moreover, information that needs some cognitive effort is retained from memory faster and better than information which is less actively processed. Consequently, openness in advertisements could increase involvement, evaluation and recall of advertisements.